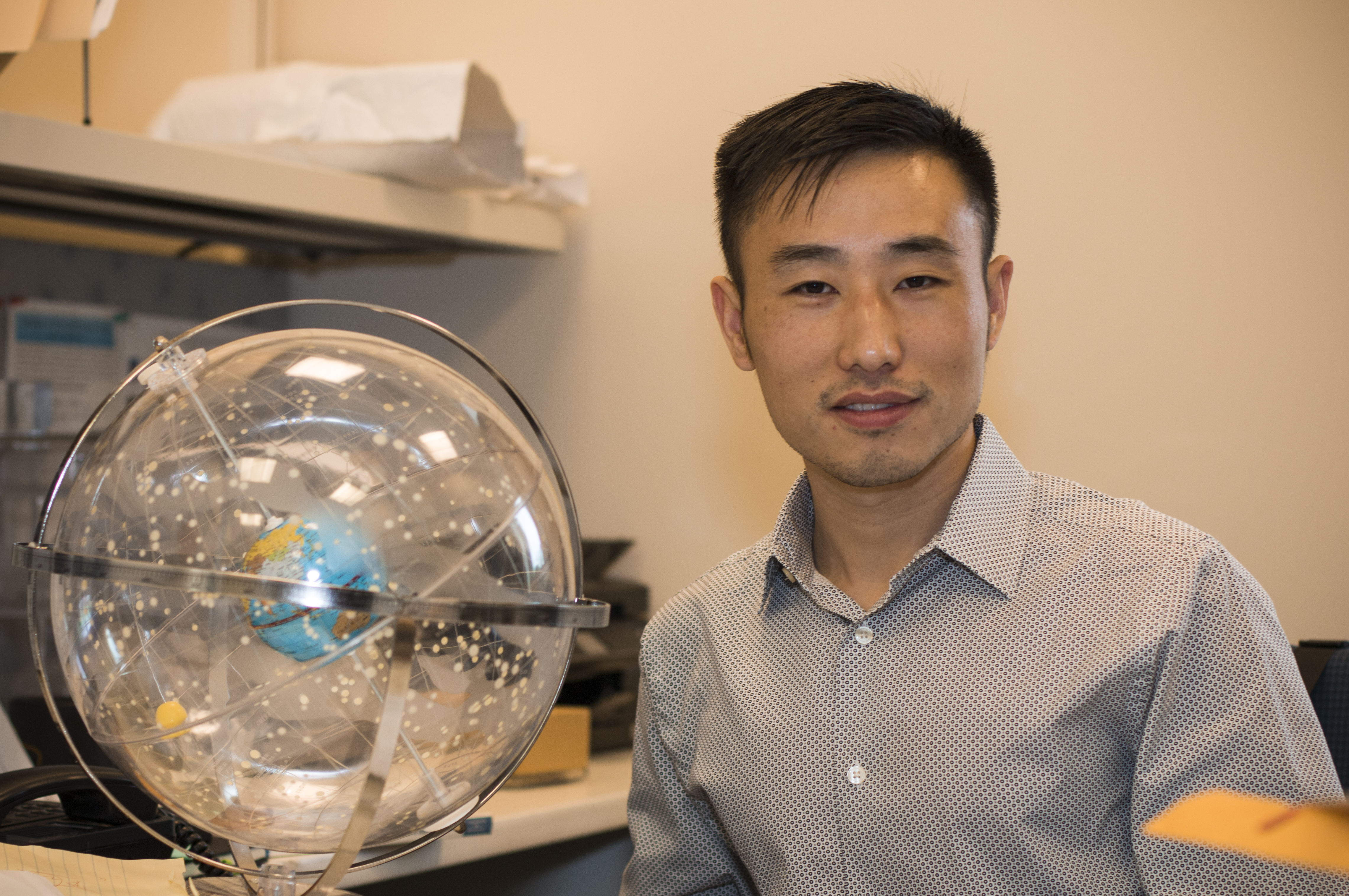

Kun Wang, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences, and other cosmochemists in Arts & Sciences at Washington University study tektites to gain insights into the giant impact event that formed the Moon.

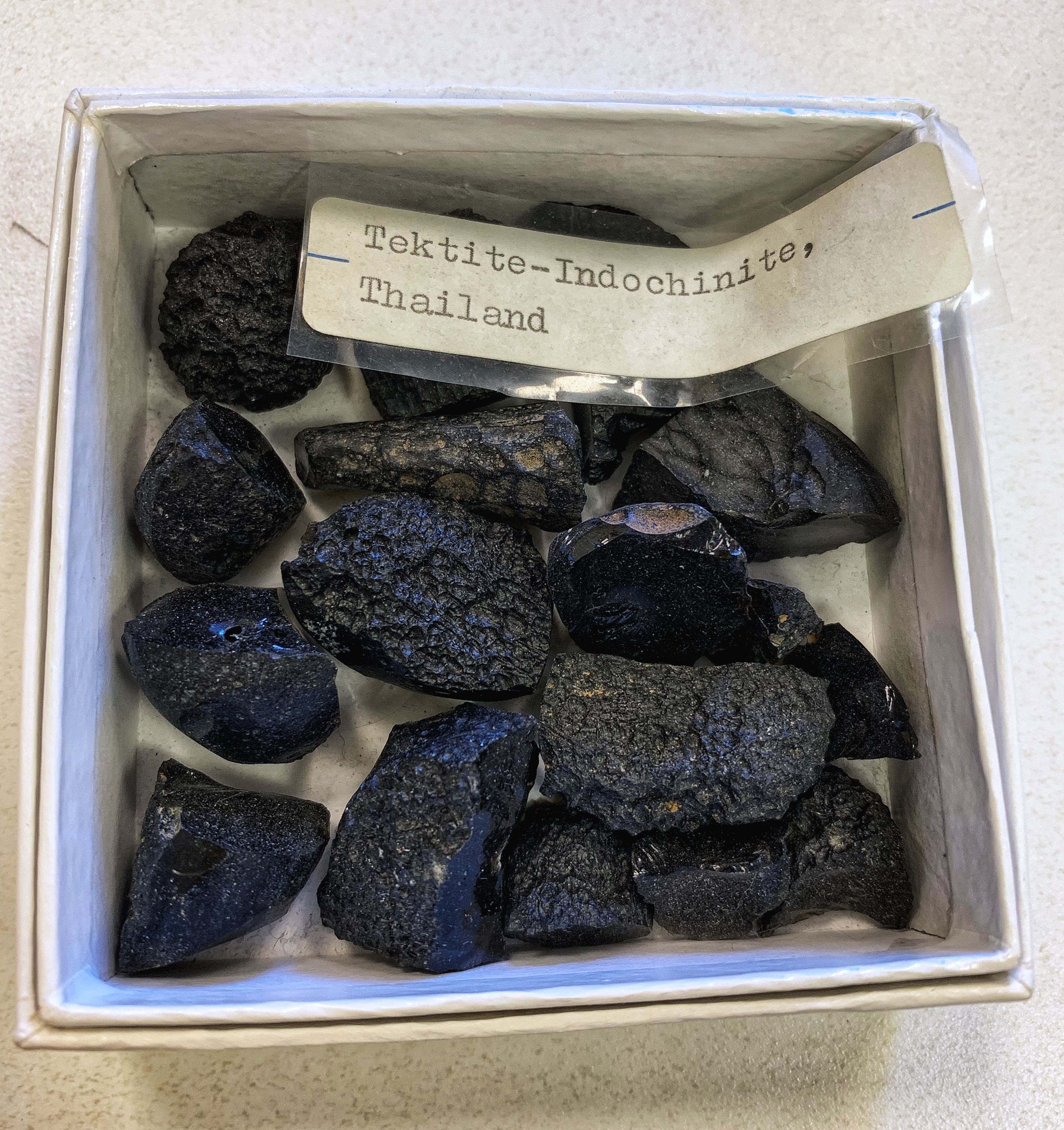

Impact events are relatively common--the objects known as shooting stars are actually small meteors burning up as they pass through Earth’s atmosphere. If a meteor is large enough, some part of it may reach Earth as a meteorite. These small impacts don’t form big craters, even if they might be large enough to devastate urban areas. However, in its long history, Earth has experienced several impact events large enough to melt terrestrial rock and send it flying for hundreds or even thousands of miles. Following these impact events, the melted rock cooled to form materials known as tektites, which can now be found in several large areas, or "strewn fields," around the world.

Scientists study tektites for many reasons, including to learn about the impact events that created them. For Kun Wang, assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, and the cosmochemistry group studying tektites at Washington University, understanding the impact process for tektite-forming events can lead to insights into the giant impact event that is believed to have formed the Moon billions of years ago. Though tektite-forming events are smaller than the Moon-forming event, the underlying process is the same.

In "Implications of K, Cu, and Zn isotopes for the formation of tektites," published in the journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta (GCA) on August 15, Wang and his colleagues present a global picture of volatile loss in tektites. They seek to answer an overarching research question: How do volatile elements change during the impact process? The team analyzed the chemical composition of tektites from strewn fields all over the world and compared their makeup with average values for the continental crust.

"We’re comparing tektites with the source of tektites, which is the upper continental crust, to see what changed during the impact," Wang said. "How do you lose volatiles? What kind of volatiles do you lose first? What kind of volatiles will lose you less of? When you lose volatile elements, you don’t lose them evenly." That’s why this average, global view is a key starting point. Once scientists understand how volatile elements are lost in tektites, they can look for the same patterns in lunar samples to determine the conditions under which the Moon formed.

In this study, Wang focused on moderately volatile elements, specifically potassium, copper, and zinc. Highly volatile elements, such as hydrogen, evaporate entirely during the tektite-forming process, but the behavior of moderately volatile elements during impact events reveals key details about the formation process for tektites and, by extension, the Moon. By establishing the expected pattern for volatile losses during impact events, Wang and his fellow researchers will be able to work backward from the products of impact events—tektites and lunar rocks alike—to learn about pre-impact conditions.

Though lunar material is fundamentally different from terrestrial tektites, Wang believes the formation process is similar enough, particularly with respect to volatile loss, for scientists to create models describing both. So far, his results support that. The sample analysis presented in this study confirms the team's model, which can account for differences in atmospheric conditions. For example, potassium, a moderately volatile element that was expected to behave similarly to copper and zinc, was shown to have almost no loss between terrestrial samples and tektite samples in this study. Wang explains, "If you compare samples from Earth and the Moon, lunar samples lose a lot more potassium, in the same range as copper and zinc. This is because they're formed in different environments and under different temperature, pressure, and oxidizing conditions."

Wang's upcoming work will expand this study by considering more samples from individual strewn fields. The team will also continue developing models for lunar formation conditions based on their sample analysis and laboratory test cases.