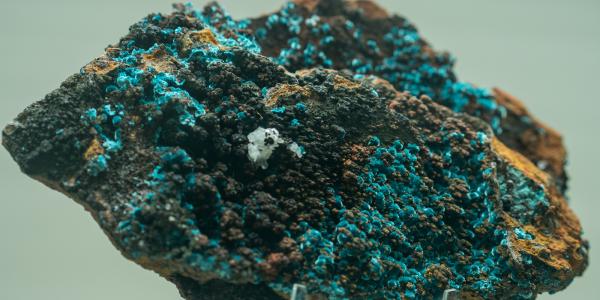

The Earth and Planetary Sciences department is fortunate to have on the first floor of Scott Rudolph Hall the glass-enclosed Grossman Mineral Museum. Curated by G. Robert Osburn, the museum contains both permanent displays and loans from local St. Louis mineral dealers who would like others to enjoy their personal collections. When you enter the museum, you will be surrounded by some of the most exquisite examples of nature’s artistry – all possible colors, some so intense they seem unreal, and shapes that range from massive and bold to so delicate they must be protected. One of the permanent displays is a captivating suite of minerals from around of the world, a gift from Scott Rudolph, who is internationally renowned for his personal mineral collection and also is the benefactor whose name our building bears.

Among the other displays within the museum are large samples of crystals clustered according to their chemistry, such as the sulfide minerals from which we obtain so many of our metals and the halides, such as the mineral fluorite, from which we get the fluoride in our toothpaste. For the minimalist, there is a collection of “thumbnail” (-sized) mineral samples representing minerals of all different chemical types. There currently are special displays on meteorites and on “Radiation – Before We Knew Better.”

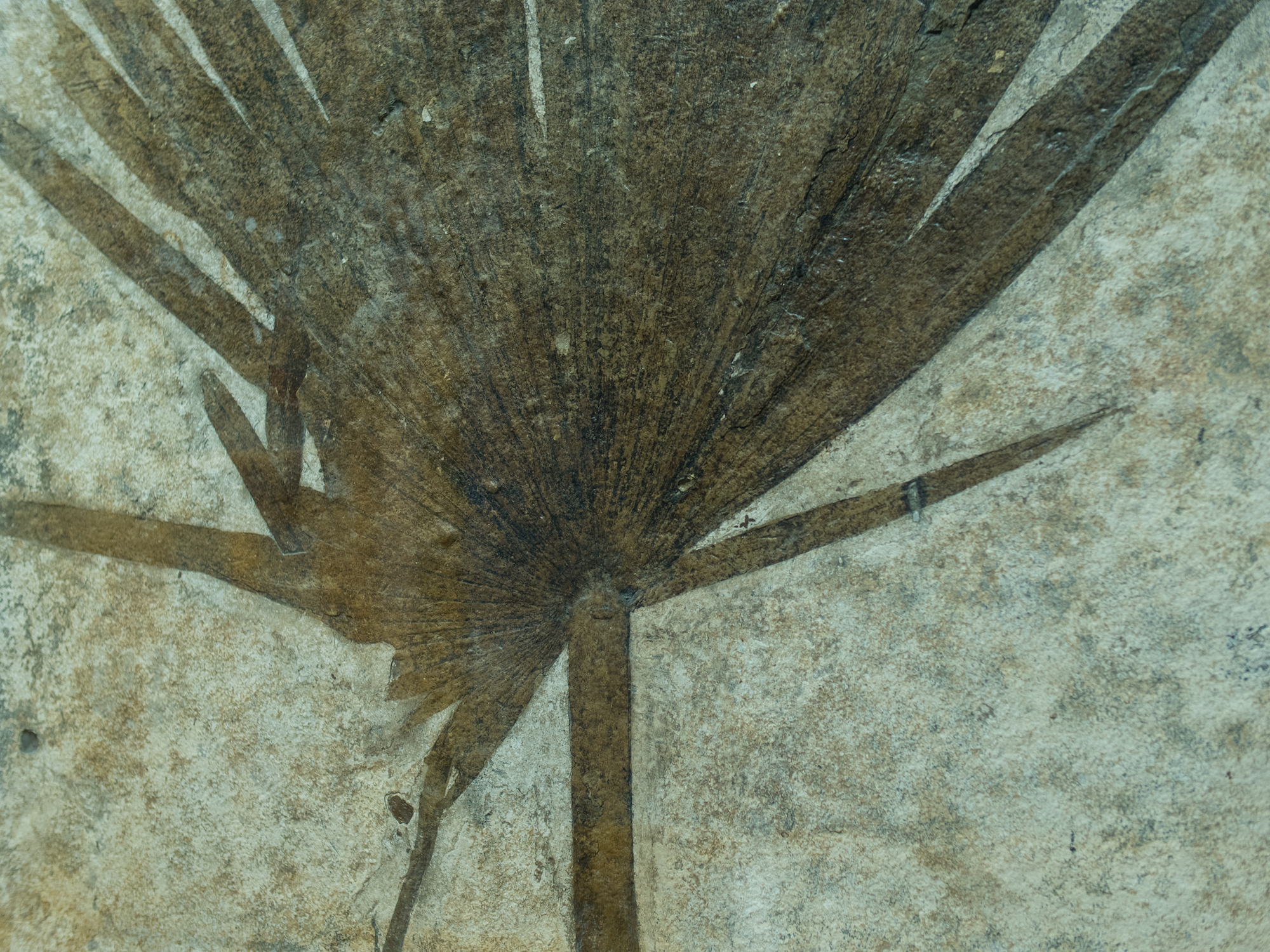

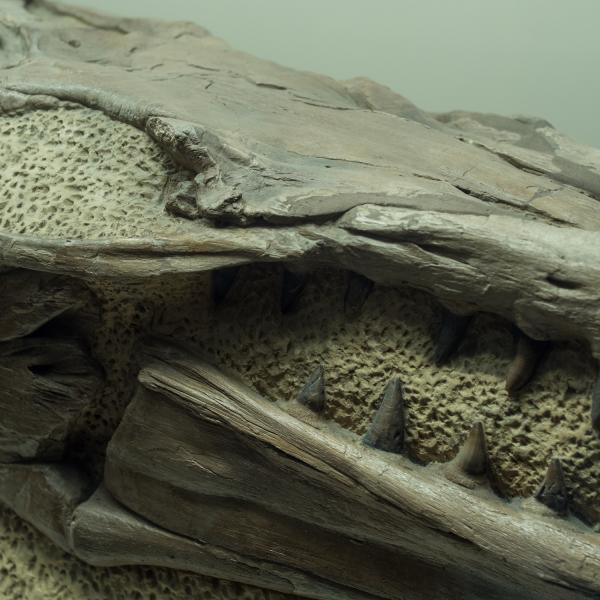

From the hallway outside the museum one can see into a ceiling-high glass case containing large fossils, including remnants of tree trunks and the complete head of a mastodon. A long glass case along the other external side of the museum displays and identifies some of the common rocks that occur locally, as along our highways. Because Missouri is the lead-mining capital of the United States, there is also an extensive display of samples collected by our students and staff and those given to us by geologists at the Doe Run company whose underground mines we have toured over the years.

If you turn completely around after looking at the minerals from the mines, you will see a small, dark hallway behind you. This short hall leads you into the Fluorescent Mineral display, otherwise known as “the glowing rocks.”